Passenger rail services in the greater metropolitan area are dominated by CityRail services operated by State Rail.

These services massively outnumber long-distance services to and from Sydney by State Rail (Countrylink) and other passenger rail operators. For this reason, and because there are currently no proposals for competitive services to be provided by other passenger rail operators in the greater metropolitan region, the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail's consideration of passenger service requirements in the region is essentially based on analyses of CityRail services and, where relevant, their interactions with freight rail services.

In 1999-2000 CityRail's total patronage was 279 million passenger trips, up by 12% from the 248 million carried in 1990 and up by 21% on the 230 million carried at the end of the most recent economic downturn in 1993. On an average weekday 940,000 trips are made on CityRail services, by about 550,000 individuals each day.

CityRail has 306 stations and a fleet of 1,456 double deck electric multiple unit carriages -- 1,138 "suburban" carriages, 80 "outer suburban" carriages and 238 "intercity" carriages -- and 44 single-deck diesel multiple unit carriages.

It operates about 3,000 train services each weekday, comprising:

|

Apart from some sidings and yards and some privately owned freight

tracks, all rail infrastructure (track, signals, etc) in the greater

metropolitan region is owned and maintained by the Rail

Infrastructure Corporation (RIC), which sells access rights to rail

operators.

The main passenger rail operator in the greater metropolitan region is the State Rail Authority, whose suburban and intercity services are marketed under the "CityRail" brand name and whose long-distance services are marketed under the "Countrylink" brand. Because they are widely known and understood, these descriptors are used in this report. State Rail also owns and operates the stations and is responsible for all timetabling and the control of all passenger and freight train movements on the metropolitan rail network. RIC and State Rail objectives Under the Transport Administration Act, RIC's "principal" objective is to ensure that the NSW rail network enables safe and reliable passenger and freight services to be provided in an efficient, effective and financially responsible manner". Similarly, State Rail's "principal" objective is to "deliver safe and reliable railway passenger services in New South Wales in an efficient, effective and financially responsible manner". Other RIC and State Rail statutory objectives, equal in importance to each other but expressly of lesser importance than the principal "safety and reliability" objectives, are:

|

As part of the overall passenger transport mix in the greater metropolitan region, rail's primary role has traditionally been to carry people relatively long distances to major centres of activity.

In 1996, for example, CityRail accounted for only 5% of all the trips made by all transport modes in the region, but 10% of the kilometres travelled and 14.5% of all journeys to work.

For journeys to work at the major centres, rail is either the dominant mode of transport, with 49% of this market for the Sydney CBD in 1996 (down from 51% in 1981), or second only to private car travel, with a mode share of 40% at North Sydney (up from 30% in 1981), 28% at Chatswood (up from 14%), 23% at Parramatta (up from 14%) and 30% for the city's centres as a whole (31% in 1981).

Rail's second major passenger transport role in the region has been to provide transport for students travelling to and from schools, universities and colleges.

For both of these major roles there is a strong concentration of patronage in the morning peak and, to a lesser extent, the afternoon peak. The latter peak period has lengthened from 2½ to 3½ hours in the last decade.

With the growth in demand in recent years, almost all peak period trains are now operating at or near their full capacity, even though there have been significant increases in the capacity provided on CityRail trains over the last 20 years.

The constraints on CityRail's capacity

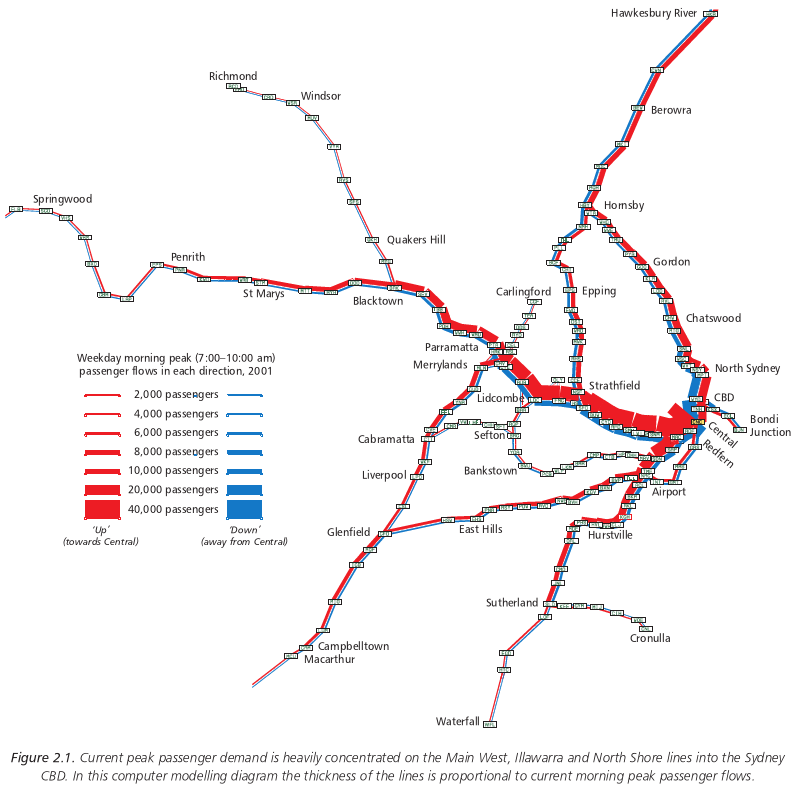

Peak patronage demand and hence the capacity provided by peak CityRail services are heavily concentrated on the main routes into the Sydney CBD on the Main West, Illawarra and North Shore lines, which combine the inputs of numerous intercity and suburban lines, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

The factors affecting passenger rail system capacity on any particular section of the rail network, and hence CityRail's ability to meet rapidly increasing patronage demand, include:

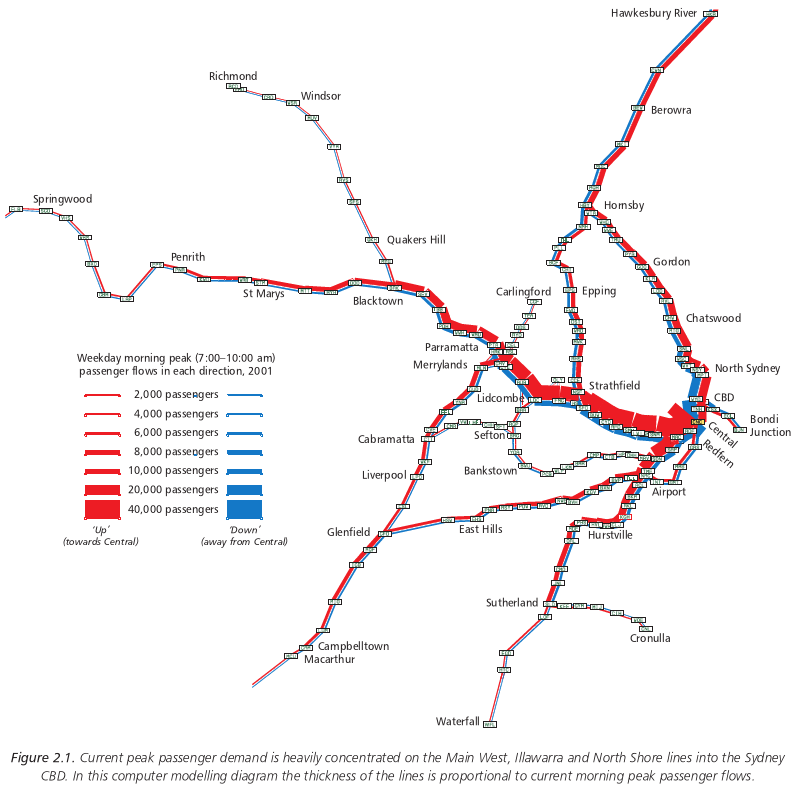

Since the 1980s State Rail has attempted to operate CityRail services in three discrete rail network "sectors", so as to minimise the impact of any service disruptions in any one sector on the rest of the metropolitan rail system (Figure 2.2):

As illustrated in Figure 2.2, while Sector 1 is still largely discrete, the growth in patronage (and hence train services) in recent years has led to considerable interaction between Sector 2 and Sector 3 services along the Main West line corridor between Granville and the CBD, and even in the case of Sector 1 rapid growth in patronage on the Illawarra line has forced some diversions of Sector 1 train services onto the City Circle, which was previously reserved for Sector 2.

This problem reflects the fact that in the last 50 years there have been almost no track amplifications on the metropolitan rail network. This means all types of services -- fast and slow, and to and from a wide variety of locations via a wide variety of routes -- are forced to share the same overcrowded tracks, with few if any overtaking opportunities and with major congestion at the routes' various junctions.

The system is rapidly approaching gridlock, as there is a finite limit on how many trains can reliably and safely use each track and, even more significantly, on how closely they can follow each other through multiple congested junctions and/or wait their turn.

The forced breakdown of "sectorisation" as train numbers have increased beyond the capacities of any one sector has been one of the factors contributing to the increased sensitivity of CityRail peak services to disruptions in recent years.

The restoration and strengthening of "sectorisation" operational

approaches is therefore one of the main emphases of the Long-Term

Strategic Plan for Rail, both in the short and medium terms and in

the longer run (see sections 3, 4 and 5). This will need to involve

both increases in the inherent capacity of the rail

infrastructure -- the equivalent of road

widening programs -- and the physical separation of the tracks and

routes used by trains operating on different existing and new

operational sectors.

As already indicated, within each of the current three main operational sectors there is a complex mix of "fast" ("express" and "limited stop") services -- generally those travelling longer distances, including intercity services -- and slower trains with a variety of station stopping patterns, including trains which stop at all stations on their routes.

This mixture of services reflects the need for CityRail to accommodate three types of demand on the one network: relatively long-distance intercity and outer suburban demand, short-haul suburban demand and "inner city distribution" demand.

It also reflects the strong desires of commuters, who often prefer to stand for long distances on crowded faster trains than have a seat on slower trains, even when the difference in total travel time is only a few minutes.

In some cases the different services are able to be segregated from

each other on four or six track sections of the

network, allowing the faster services to overtake. In most cases,

however, the almost total absence of track amplifications and

junction grade separations in the last 50 years means this option is

not available, and complex and disruption-sensitive timetabling is

required.

As the number of trains has increased, the operational robustness of timetables with complex mixes of types of services has declined.

Again, the segregation of services to overcome this difficulty is a

major focus of the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail (see sections 3,

4 and 5).

Other operating constraints

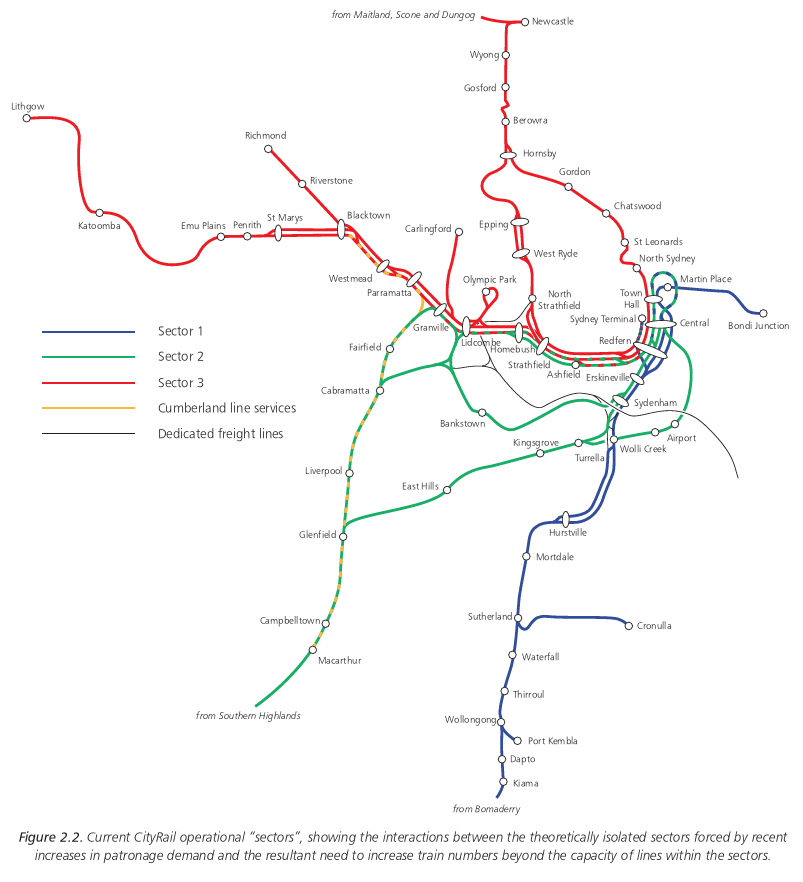

The other principal constraints on current CityRail operations, described in detail in the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail, are (Figure 2.3):

For example, there are already 20 northbound trains per hour crossing the harbour bridge in the morning peak, so unless the inherent capacity of this line can be increased (see section 4.3) this route cannot be used to accommodate any further growth in the number of trains entering the CBD in the mornings.

Again, this problem reflects the fact that in the last 50 years there have been almost no track amplifications on the metropolitan rail network. The temporary relief afforded to the network as a whole by the introduction of double deck trains and to the City Circle by the construction of the Eastern Suburbs Railway in the 1970s has now been almost totally absorbed.

Because trains using the key junctions have to be very closely timetabled during peak periods, with complex merging and conflicting train movements, there can be acute service reliability problems, as even a slight delay in one train service can very quickly delay large numbers of trains. This effect may not be as visible as at a heavily congested road intersection, because the signalling system automatically holds the trains well back at safe separations, but its impacts are just as real.

The problem is compounded when the conflicting or merging train services are operating on different "sectors", such as on the Main West corridor and in the inner city and CBD.

In essence, the locations of facilities for minor routine train maintenance reflect the requirements of passenger rail operations some 50 to 70 years ago, when the train maintenance depots were at or near the extremities of suburban rail services, but not those of today's geographically extended operations.

In summary, the metropolitan rail network is now so congested that peak CityRail operations are extremely finely balanced, with minimal margins before delays occur and escalate.

The Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail explicitly addresses all of the

factors described above, along with other major factors in poor

on-time running performance: rolling stock failures, the increased

frequency and severity of rail infrastructure failures, and

limitations on incident response and recovery capabilities.

Service reliability and on-time running performance

The principal measure used by State Rail to monitor the punctuality

or "on time running" of CityRail services is the proportion of peak

services arriving at their destination within 3 minutes of the

timetabled time in the case of suburban services and within 5 minutes

in the case of intercity services.

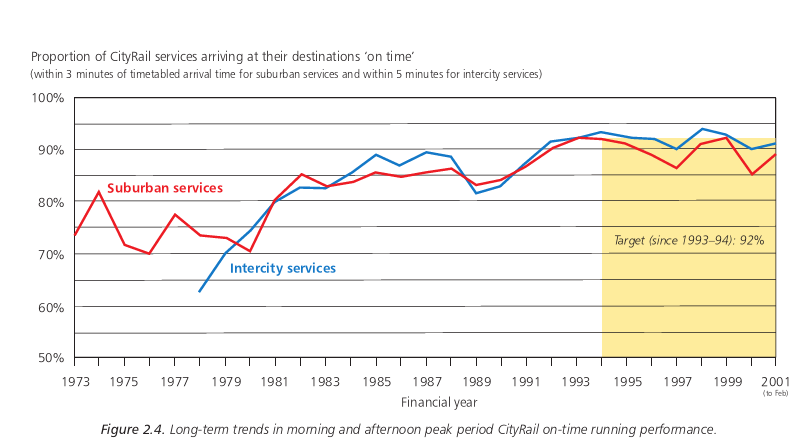

Since 1993-94 the target for this measure has been 92%. Although on-time running has generally improved over the last 25 years (Figure 2.4), it declined in 1999-2000 to levels not experienced since the late 1980s, and despite a strong recovery during 2000-01 on-time running is still only about 90%, below State Rail and customer expectations.

On-time running performance is affected by:

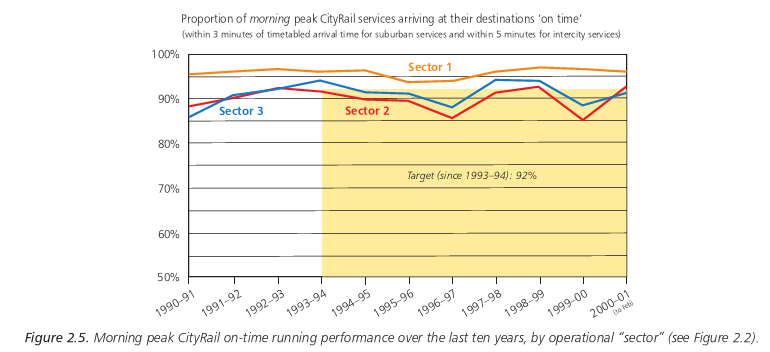

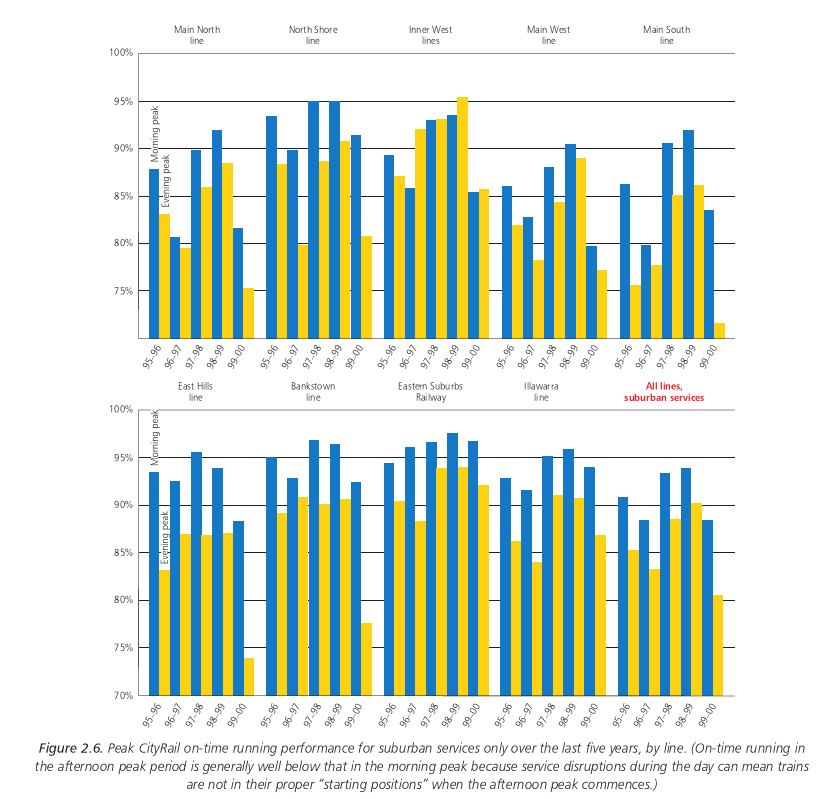

This is well illustrated by the fact that on-time running is poorer on the rail corridors in Sectors 2 and 3, which have the most complex and inter-woven operating patterns and the greatest number of flat junctions, than on Sector 1 lines, where service patterns are less complex and are still comparatively isolated from the other sectors (Figures 2.5 and 2.6).

The reliability of the CityRail fleet is hampered by the mix of different types of rolling stock, the age of a significant proportion of the fleet and inadequacies in train maintenance facilities, equipment and parts inventories. Until recently it was also hampered by deficiencies, now being redressed, in the maintenance and overhaul regimes for key components such as doors.

The Government has recently made some important funding commitments to enable these issues to be addressed in the short term, as discussed in section 6.3.

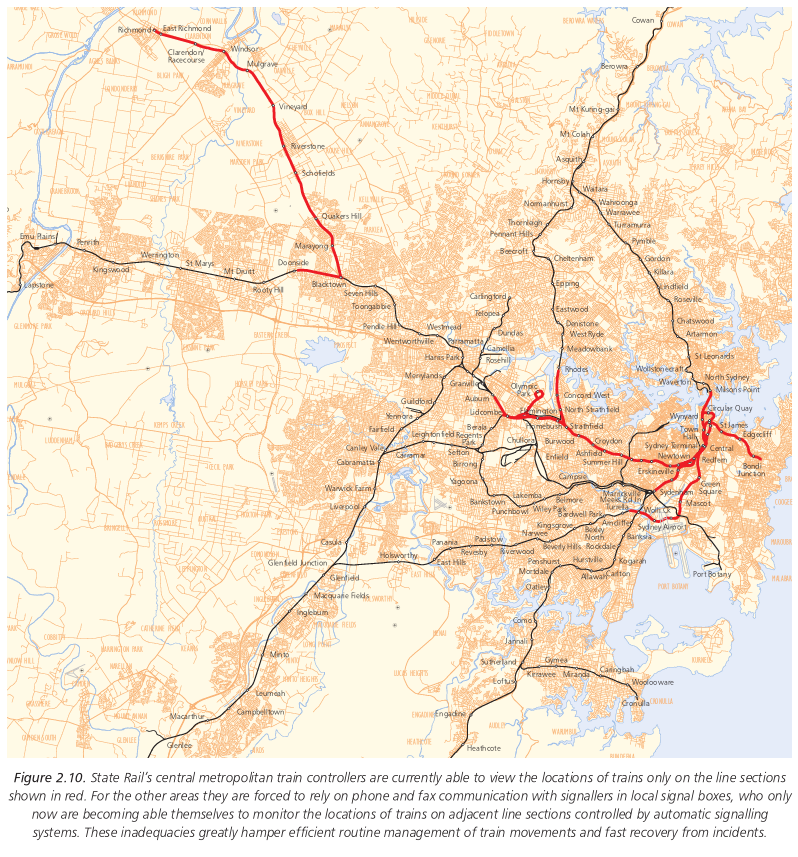

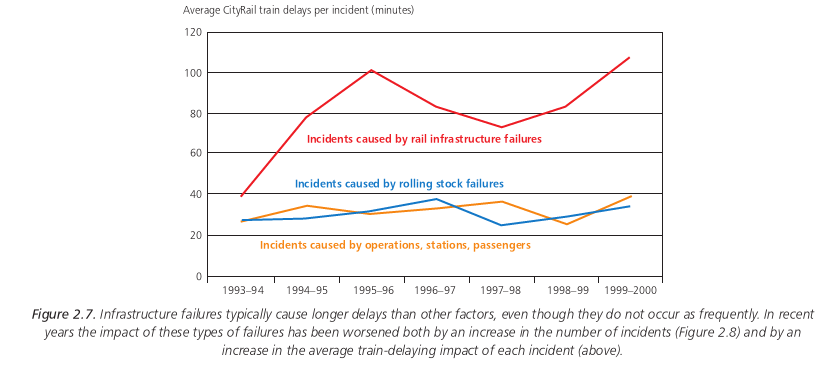

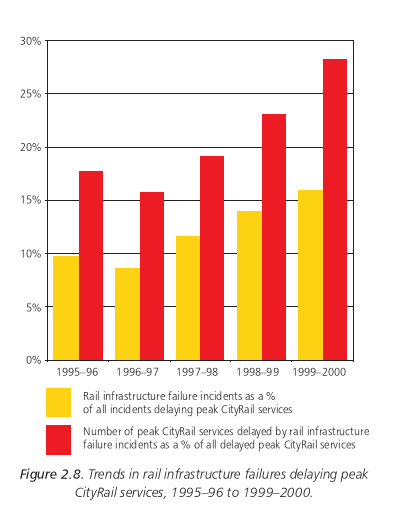

Although infrastructure failures account for only 15% of all the incidents delaying peak CityRail trains, they usually cause longer delays than the other factors (Figure 2.7), and in 1999-2000 they were responsible for almost 30% of CityRail train delays, with both the number of rail infrastructure failures and their impacts on CityRail services being well up on earlier years (Figure 2.8).

About three-quarters of the rail infrastructure reliability problems delaying CityRail peak services are associated with track and signalling failures at junctions.

The factors contributing to the increase in rail infrastructure reliability problems in recent years are discussed in section 2.3 below, and strategies to address these problems are summarised in section 4.10.

Again, the Government has recently made some important funding commitments to improve rail infrastructure maintenance in the short term, as discussed in section 4.10.

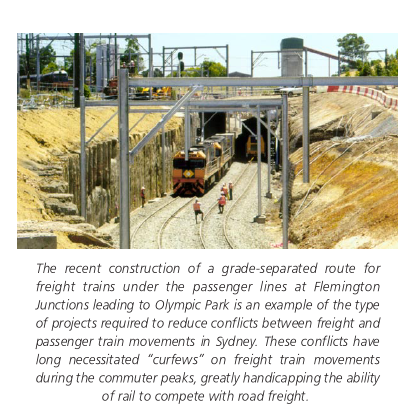

Most of the railway lines used by freight trains in the greater metropolitan region are shared with passenger services, although there are dedicated freight lines between North Strathfield Junction, Flemington Goods Junctions, Chullora, Sefton Goods Junction, Enfield, Rozelle and Port Botany (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Rail freight services within and through the greater metropolitan region comprise:

The effects of this curfew are most critical on the Main South line between Macarthur and Sefton Goods Junction, part of the main routes connecting Melbourne and Adelaide with the Sydney freight terminals and ports and Brisbane, because the busiest times for freight trains arriving from Melbourne coincide with the busiest times for CityRail commuter services from Campbelltown and Liverpool to the city.

On the Main North line to Newcastle (and on to Brisbane) the

constraint is less significant, because there are fewer freight

trains and operating patterns are different. For this corridor it is

likely that a guarantee of two freight train "paths" per hour for 22

hours per day in the contra-peak direction -- i.e. with a two-hour peak

direction "curfew" -- would suffice to meet anticipated freight

demand, and even this is regarded by Rail Infrastructure Corporation

as a long-term target, rather than one to be achieved in the metropolitan area

in the short to medium term, because there are other, more severe

constraints on Sydney-Brisbane freight services further to the north,

on the single-track North Coast line.

Investigations over the last four years have identified the most cost-effective ways of progressively reducing the curfews on the Main South and Main North corridors, including the construction of a new bidirectional track from Macarthur to the Sydney side of Cabramatta Junction for use primarily by freight services. These works, which are now the subject of detailed design and environmental studies but will proceed only if Commonwealth funding is provided, are discussed in sections 4.4 and 5 below.

Other constraints on rail freight services in the greater metropolitan region include:

The capacity constraints affecting Hunter coal freight services -- and by implication CityRail and long-distance passenger services in that region -- are potentially severe, but are being addressed in separate RIC capital works programs and studies and are beyond the scope of the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Rail.

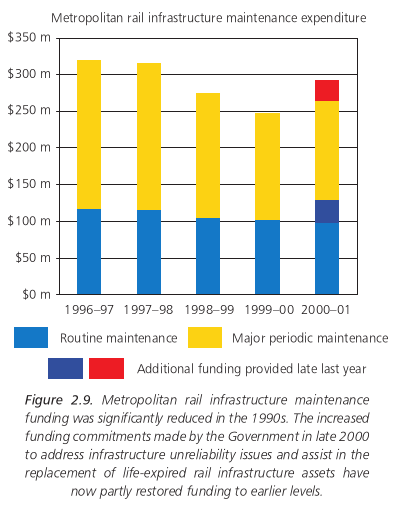

One of the main factors in this degradation was the downgrading of many "major periodic" maintenance programs during the 1990s. Although reductions in major periodic maintenance expenditures (Figure 2.9) were intended at the time to be at least partly counterbalanced by efficiency gains, and funding levels were reduced in this expectation, in practice the anticipated gains were only partially realised, even on lines maintained by the private sector after competitive selection processes. Because of the reduced funding, and also because other projects were regarded as having a higher priority at the time, the scope of major maintenance programs was severely curtailed.

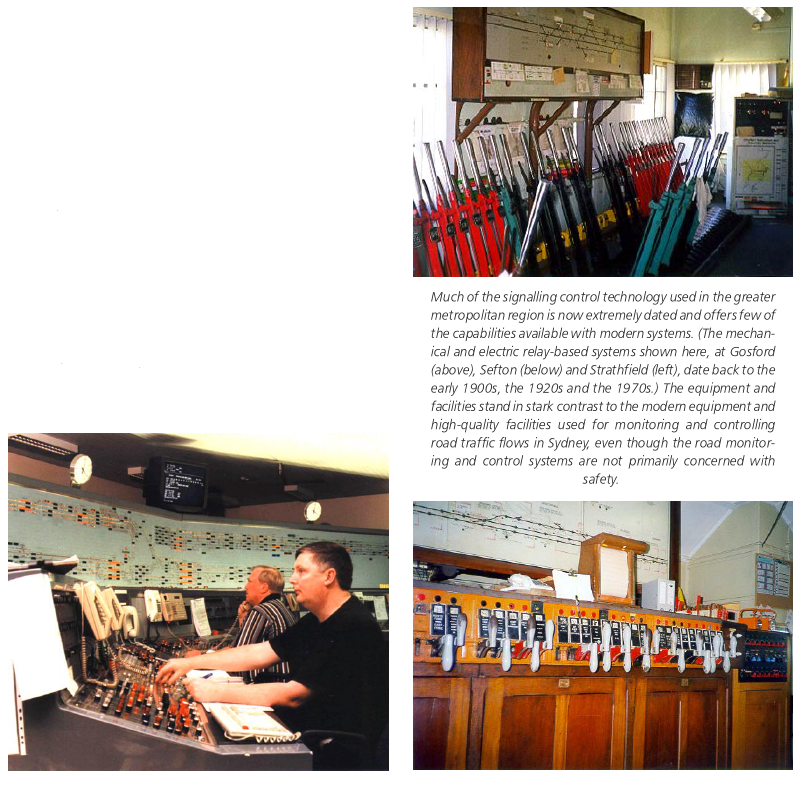

These programs -- which can be traced back to upgrading works initiated

around the time of the Granville disaster -- included a track

strengthening and concrete resleepering program, a signalling

modernisation program, an overhead wiring modernisation program, a

junction renewal and upgrading program and ballast cleaning, track

tamping, rail grinding, timber resleepering and rerailing programs.

The downgrading of these major periodic maintenance programs has now resulted in a serious maintenance backlog, degraded asset quality and reliability and increased day-today routine maintenance costs.

Even with increased funding, this backlog will be difficult to overcome, as Rail Infrastructure Corporation's major plant items are old and incapable of meeting production requirements (many of the items which will have to be used over the next couple of years have been taken out of "mothballs") .

The actions and expenditures required to redress this situation are discussed in section 4.10 of this report.

The major deficiencies in metropolitan rail safety systems, almost all of which have been or are now being addressed, have been: